Freelance health journalist and former neuroscientist interested in a wide variety of life science topics. David also writes for The Guardian, BBC, National Geographic, NBC News, Wired, TIME and others.

Since the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies around the world have invested staggering sums of money in the search for a treatment which might halt or reverse the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia, and the World Health Organisation estimates that it comprises somewhere between 60 and 70% of global dementia cases.

But despite billions spent on the search for a cure, there has been precious little progress. Time and time again, highly touted drugs have failed in late stage clinical trials, and an increasing number of scientists have begun to consider an alternative approach. Rather than attempting to halt Alzheimer’s in its tracks, is it more worthwhile trying to prevent it developing, before the symptoms take hold?

Around the globe, different research institutions and companies are racing to try and develop an Alzheimer’s vaccine, an immunisation which can be administered to those thought to be at risk. If they succeed, it would be a game changing moment in the fight against the disease.

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, scientists have just launched a Phase I clinical trial of a nasal vaccine which will attempt to activate white blood cells in the lymph nodes in the neck through a vaccine adjuvant called protillin. It is hoped that these cells can then clear toxic forms of the beta amyloid protein – the main Alzheimer’s drug target – in patients with very early stage Alzheimer’s, before it clumps together into plaques, causing a steady process of neurodegeneration.

Based on promising results in animal models of Alzheimer’s over the last 16 years, it is the first time that such this particular vaccine technology has been tested in humans. Scientists are particularly intrigued as there is existing evidence showing that stimulating brain immune cells through vaccinating the elderly against other diseases can have a protective factor against Alzheimer’s.

“This is a very different type of vaccine than any tried before,” says Rudolph Tanzi, an Alzheimer’s researcher at Harvard University, who has 14,372 topic citations for beta amyloid on Insciter.com.

“The idea here is to use the microbial-derived agent protillin to promote activated monocytes to enter the brain and clear amyloid. Our recently published data which shows that pro-inflammatory cytokines actually improve cognitive trajectory in people with amyloid in their brains, and the fact that many vaccines have been shown to protect against Alzheimer’s, actually supports this idea.”

The Boston trial is just one of many Alzheimer’s vaccine projects taking place around the world. Lausanne-based pharmaceutical company AC Immune has a vaccine in Phase II trials which attempts to prevent the formation of amyloid plaques. Neurologists at the University of South Florida have had successful results in mouse models of Alzheimer’s with a vaccine which uses dendritic cells to guide the immune system to target amyloid, and are now seeking commercial partners to fund human trials.

While Alzheimer’s vaccines have been studied in the past with limited success, neuroscientists believe that the current range have a far greater likelihood of succeeding because they are being tested on patients in the very early stages of cognitive decline.

“I think this is exciting,” says David Holtzman, a neurologist at the Washington University School of Medicine, who has the highest influence trajectory for beta amyloid on Insciter.com. “Now that trials like this are moving earlier into the presymtomatic phase of the disease, I think they will have a much better chance to see clinical efficacy.”

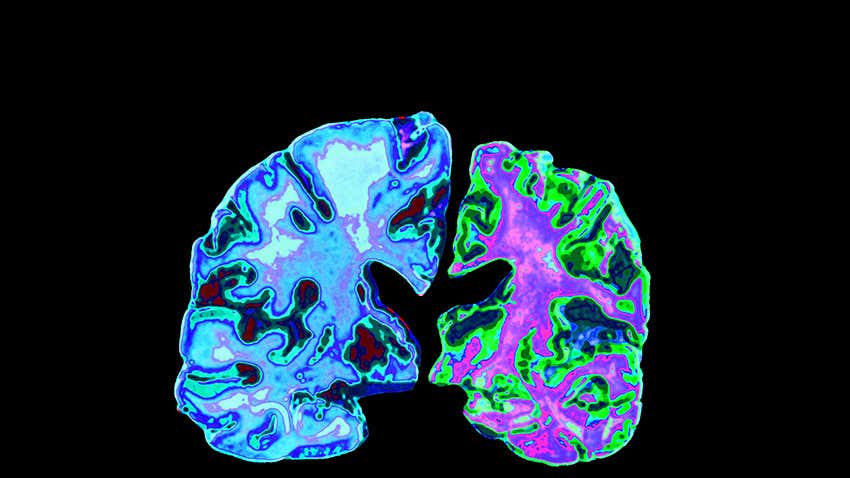

While amyloid plaques in the brain are the main hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, the other major disease signature is the steady build-up of a protein known as tau. Certain changes can cause tau to accumulate inside axons, which affects the ability of neurons to communicate with one another.

As a result, AC Immune are also developing a separate vaccine, which is currently in Phase 1/11 trials, which attempts to prevent tau accumulation, while other researchers are looking into immunotherapies which could possibly slow down disease progression by removing tau from the brain.

Neuroscientists suggest that the amount of tau accumulation in the brain could also serve as an indicator for whether vaccines targeting amyloid will be effective or not. “A likely critical drive of brain damage is tau accumulation,” says Holtzman. “I suspect that if one removes amyloid once there is substantial tau accumulation as well as significant nerve cell loss, then it is likely too late to see a significant clinical benefit. Going earlier when there is amyloid deposition but not much tau accumulation or neuronal loss seems a much better approach.”

Scientists agree that for Alzheimer’s vaccines to be successful, they need to be administered to patients as early as possible in the disease process. Chuanhai Cao, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of South Florida, suggests that there needs to be an annual screening program for all over 60s, using a combination of brain imaging scans and blood tests for toxic forms of amyloid, to detect those in the very earliest stages of cognitive decline.

Dennis Selkoe, a neurologist at Harvard Medical School who ranks No.1 for topic citations for beta amyloid with 36,356, says that blood tests are beginning to be developed which are capable of detecting whether different forms of amyloid area in the brain, before Alzheimer’s patients have begun to display symptoms.

Having such tests available will make population screening programs far more practical and economically viable. In the past, the only means of detecting the presence of amyloid was through collecting cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is both invasive and expensive.

“The challenge has been in translating CSF to blood plasma tests,” says Selkoe. “But research has shown that it can be done, and we now just need widespread validation in multiple cohorts, which Is underway in a number of labs and companies.”

Tanzi believes that screening and early detection is the way forward in tackling Alzheimer’s, using the comparison of cholesterol build-up and heart disease.

“We need to target amyloid as early as we target cholesterol to prevent heart disease,” he says. “Once you have heart disease, you may take cholesterol lowering drugs to help prevent future blockages, but you would not expect it to make the heart better. Likewise, removing amyloid would not be enough to make the brain better, but if you do so as soon you know you have amyloid accruing in the brain, you can probably nip the disease in the bud.”

Keep up to date with the latest news in the biotech investment community.

© 2021 Insciter. All rights reserved. Insciter is a technology application which serves as a search engine and data provider

Trading name of Layer IV Limited. Registered in England and Wales No. 11737675